Wicked problem. Beautiful living afterwards

16 May 2014 • John de Croon

risk management, policy development

In my column on 18 April of this year I discussed the tricky balance between risk and potential benefits of shale gas. In that column has been described that parties did not agree on the solution, but agree on natural gas will run out in the future. But what is the case if the parties do not agree on the problem? That's what this column about. This kind of problem is called a wicked problem. The theory on this is quite a few years old[1], but still surprisingly actual. And because it's Friday, it's a beautiful day to solve such complex problems for once and for all...... it has taken long enough.

Rittel and Webber already wrote on the complexity in defining problems and locating problems in 1973. When something is perceived as a problem, a measure must be defined which must be executed and thus with which the future can be affected. For technical problems, you can define clear criteria for the solution to meet. For example, if the traffic capacity on a bridge is insufficient, then we can expand the capacity by replacing the bridge. The bridge must meet a number of minimum (or maximum) requirements. Consider the vertical clearance relative to the water level, the width, the deadweight, the minimum capacity for traffic, the maximum angle for traffic and maximum maintenance costs per year for a particular use. Potential solutions can then be tested against the specific requirements with which the problem can be solved. But what if we do not agree on the problem?

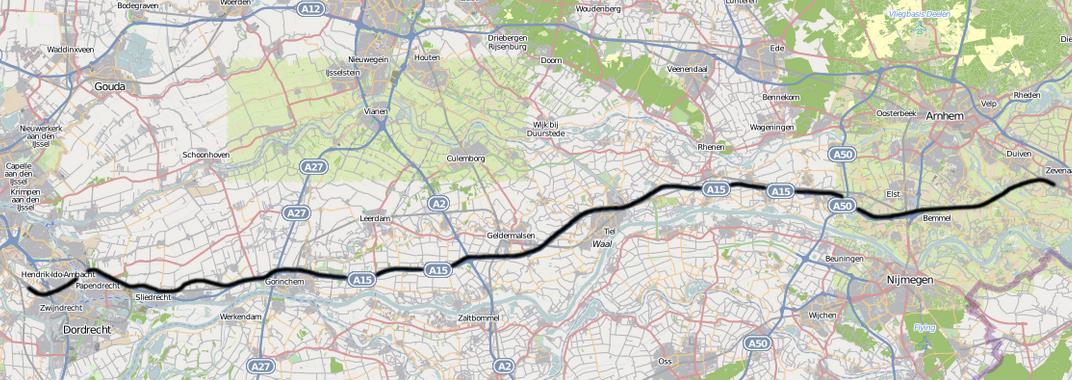

About 30 years ago there were signs that road and water traffic would cue from the Rotterdam harbor (which would be extended with a second Maasvlakte) to the hinterland in Europe. Also, the vision arose that in the longer term there would be more competition from Antwerp via the rail track ‘Iron Rhine’ to the German Ruhr area and beyond[2]. A better connection for Rotterdam was therefore needed and the idea for the ‘Betuwelijn’ arose: a specific rail track for cargo between Rotterdam and Germany. But not everybody did agree on the problem[3]. So this is a wicked problem.

Figure: http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Betuweroute#mediaviewer/Bestand:Spoorlijn_kijfhoek_zevenaar.png

Every wicked problem has some similar characteristics. As problems become more complex (and thus not only technically but also socially and politically), it becomes increasingly difficult to find a solution and implement it. Rittel and Webber state that finding the problem is the same as finding the solution: the formulation of the problem is the problem. The problem with wicked problems is that the solutions are not right or wrong, simply because they cannot be assessed against specific design criteria which have a uniform shared definition. One solution is thus - depending on who you ask - better or worse than another solution. One party may find the solution not good enough, while another party believes it is good enough[4]. For instance in case of the Betuwelijn the rail transporters saw this as an opportunity to increase their sales. Before the Betuwelijn existed, a few people lived nicely on the country side, or 'afterwards' as we call it in Dutch. The people who had to leave their homes due to the construction of the Betuwelijn were of course not so happy. So the solution to a wicked problem has undesirable consequences, which may be greater than the original problem for certain stakeholders. But the issue remains that not everyone agreed to whether there was a problem.

As with other wicked problems, the situation of the Betuwelijn was unique. There were no previous similar experiences that could prove that the solution is 'correct'. Another important characteristic associated with solving a wicked problem is that the design process is not linear as it is with a normal problem, so via a definition of a problem, a program of requirements, specification, design and construction. In case of a wicked problem these steps are run through in iterative cycles. What is striking in case of the Betuwelijn, is that the government has decided to construct the entire track at once[5]. This implies a (more or less) regular design. However, there were quite a few changes during construction, indicating that for parts the cyclical process was followed. Thus gradually the transfer station of Valburg was deleted and tunnels were added near the town of Zevenaar. The Betuwelijn finally has been realized for € 4.7 billion, while in 1992 the expenditure was estimated at € 2.3 billion (see the mentioned wikipedia site).

Couldn’t it be done differently? With regard to the definition of the problem it is not so certain. The interests were so far apart that probably no agreement would be reached to the problem definition between all involved. So it is not so strange that the administration, given the economic interests, at one point makes a decision. And the administration has that power after democratic elections.

However for the realization a note can be made. In the problem definition it had to be clear that this was a wicked problem and that therefore much iteration would be required before one came to a solution. So it is strange a decision is made so early in the process on the entire rail track. A phased approach on decision-making and implementation (so containing parts of the route) would have been much more logical. Then we actually come back from the column of four weeks ago, where we stated it is sometimes better to postpone potential distress associated with a measure.

But that's hindsight, and it is beautiful to live ‘afterwards’ (so on the countryside). Although the people who have had to leave their homes for the Betuweroute will possibly think differently. Now I just remember I did not crack the problem of wicked problems ..... for that I need the weekend I'm afraid.

[1] Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber. Policy Sciences 4 (1973)

[4] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wicked_problem

John de Croon is partner at AssetResolutions BV, a company he co-founded with Ype Wijnia. In turn, they give their vision on an aspect of asset management in a weekly column. The columns are published on the website of AssetResolutions, http://www.assetresolutions.nl/en/column

<< back to overview

|